I know from experience what it means to be hungry

The devil of money has been present in literature for more than two and a half thousand years

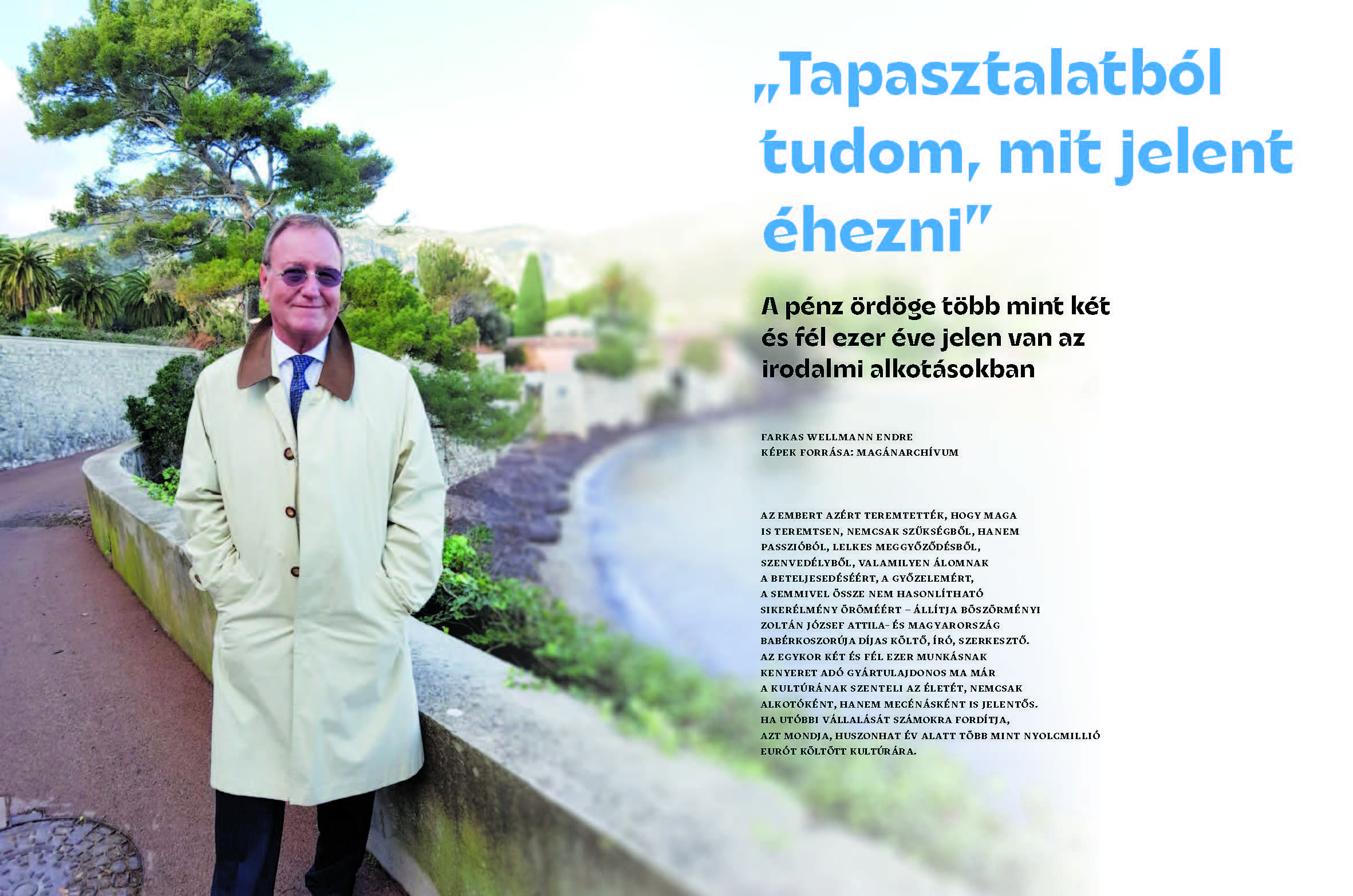

Man was created to create himself, not out of necessity, but out of passion, enthusiastic conviction, passion, for the fulfilment of a dream, for victory, for the joy of an incomparable experience of success - says Zoltán Böszörményi, poet, writer, editor.

Once the breadwinner of two and a half thousand workers, the factory owner now devotes his life to culture, not only as a creator but also as a patron of the arts. If he puts his latter commitment into figures, he says he has spent more than eight million euros on culture in twenty-six years.

Literature and money - two separate worlds. You are at home in both, and you are successful in both. How do the two fit together in your soul?

Over the last century and a half, it has become increasingly obvious that there is money to be made in literature. Publishers are also trying to select authors and their works in order to make as much profit as possible. Books, like any other product on the market, are supply and demand. Some authors do not create for money, but they make a fortune. Thomas Mann, for example. At the end of his life, he was worth at least three million in today's dollars. Other authors live modestly, write very good books, but the market ignores them. Towards the end of his life - he collapsed and died in a doorway in Paris - Stendhal complained to friends that his novel Red and Black had sold barely 200 copies, while Gustav Flaubert's Mme Bovary was being sold by the thousands from under the counter. We also meet an author in world literature who always wrote for money, yet died poor. I am thinking of Balzac. And in Hungarian literature, Milan Füst was supported throughout his life by his rich wife. A good writer is not necessarily successful, and a less good one can be a world success. The only book by my late friend István Vizinczey, In Praise of Older Women, has lived very well throughout his life. His literary worldview is a mixture of successful and unsuccessful writing careers, good and not so good works. Money, of course, plays an important role in all cases, because writers have to make a living. When I was a factory owner, I had little time to read, let alone write. The business world is alienating, it keeps your adrenaline pumping, it's hard to let go because one crisis follows another. You have no peace of mind, you can't concentrate on anything else. You're happy to have a quiet weekend to sleep it off. For as long as I can remember, I've never done anything for money. Not even when I was an industrialist. What mattered was success, producing a product that was excellent and sold at a good price. But I never calculated or cared what my share of the profits would be if my company made ten million dollars a year. All that mattered was success. In literature, success is the reader. The more people you can reach, the greater your pleasure. The big question of whether I've written a good book is always a matter of doubt. I think for every writer, this can be the eternal dilemma. Sándor Kányádi, even in his old age, asked himself many times: had he really created something great and significant? But he knew that he had. And yet...

You have decades behind you in both fields. I think a common point in both worlds might be that they are both about building something. Building is hard. But after all these years, how do you see it making sense? If so, which one does?

In the business world, too, it's all about creating value. You have to create something to move society forward. If you do a good job, it goes without saying that this will generate money, it will create financial benefits, the more you earn, the more you can invest in research, development, modernisation of means of production. This is also the sine qua non for the quality of your products. It has practical benefits, you are serving humanity. To design, to research, to develop, to build, to serve, to create value - these are the big buzzwords. But literature is amoeba. It can affect the human consciousness, the psyche, it can influence one's value judgements, it can give one advice, it can show one side of reality, because the other is always hidden, sublimated, transcendental. It creates an intellectual, emotional world, it has a soul-forming function. It directs the spotlight of the spirit on the beautiful, the aesthetic. It points to the polarity of things, to good and evil. It conjures up a mood, dazzles, turns the knife of thought in you. Plato, Aristotle and many others considered literary and artistic creation to be of divine origin. I would add that, in addition to divine inspiration, a writer needs will, craftsmanship and commitment. As I said, creation is also a product that can be sold, hence the obvious conclusion. Which is more worth "producing"? I do not know the right answer. Both can cause great disappointment in one's life. In the case of the literary product, the work of art, I think this disappointment can be more pronounced. It can cause more pain than anything else. See the case of Dániel Berzsenyi, who did not recover from Ferenc Kölcsey's criticism for years.

Literature and money, so to speak, are two opposite dimensions. Spirit and matter. Obsession and security of existence. Eternal life and relative earthly prosperity. Which means which in your value system?

Success and money are not always good for people, whether they are industrialists, scientists, businessmen, artists or poets. It takes away your inner motivation, the privilege to cultivate what equals your life for your own pleasure, flowing, fully immersed in it. Man was created to create himself, not out of necessity, but out of passion, out of passionate conviction, out of passion, for the fulfillment of some dream, for victory, for the joy of an incomparable experience of success. For me, money was a derivative of this aforementioned experience of success. I don't say that I didn't feel some satisfaction, but I never rejoiced in it, because I still consider it a very dangerous instrument. You have to learn to use it. And I have still not managed to do so to this day. So much for money. As for my literary achievements, well, there is still a doubt in my subconscious. They are annoyed by me, they are not looking for literary value in my work. They look at my books with some inexplicable aversion, and I have friends who don't even bother to read them. And the everyday reader never sees my books, because they are tucked away in the corners of bookshelves, never on the prominent tableau, the book island of contemporary literature. So how do they know about it? Who's going to search the bookshelves? I complained about this fact in one of the big bookshops. I was told that new books are kept on the novelty shelves for a week. One week! After that they are shelved. On my website, many of my writings have been read by thirty, forty, fifty thousand people. So I am doing something right. Many of my books and writings can be downloaded for free from my website. And the number will only increase in the coming years.

Free literature? - you might ask. What does that look like? Well, it looks like this. Anyone who wants to read it can. I didn't write it for money.

As long as the world has been the world, among the eternal themes of poetry is wealth. What do you think would happen in a world where every artist had access to unlimited amounts of money?

The "devil" of money has been present in literary works for over two and a half thousand years, and its theme runs through Hungarian literature. I mentioned Balzac above, but it is impossible that most of us will not remember Mihály Csokonai Vitéz's exclamation, which has become a catchphrase: "He who becomes a poet in Hungary is also a fool!" Tempefői, the poor poet, wanted to gain his social status through his poems, he wanted to earn money. In his iconic poem, Ady's Fight with the Great Lord, he calls money the pig-headed Great Lord. But the money motif also appears in the poetry of Janus Pannonius. Sebestyén Tinódi, write and say, earned his living with his lute, mostly receiving accommodation and board for his "performances". Sándor Petőfi, János Arany wanted to get rid of the yoke of making money. Attila József was constantly struggling with financial and existential problems. Mikszáth, Móricz, Kosztolányi earned their living through hard journalistic work. In terms of earnings, I think the best thing for writers was under socialism. But they had to pay a heavy price for their "grind", perhaps the most important one: giving up free speech. Which reminds me that a good friend of the Roman emperor Augustus, the wealthy Maecenas, gave the empire's singers a cash reward, and was perhaps the first to provide them with an annuity. One of Stalin's death lists is in facsimile in my novel Torn to Shreds, of which Isaac Babel was tenth. He was shot in the back of the head. But Bulgakov escaped execution. He did not praise the empire, but compared Stalin to the French Sun King Louis XIV.

What if writers and poets had unlimited access to money?

No, I can't imagine such a thing. Unlimited money is not good for anyone. Too much money takes people's minds, strips them of their humanity. It corrupts them. Everyone has to work for a living.

You have to work to enjoy life. Work means not only hardship but also real pleasure, and in Kantian terms: freedom, autonomy of moral action.

Our cultural life today is also polarised by money, by the various ways in which culture is financed. What do these public conditions look like from your point of view, who is not confronted with penny-pinching problems? Can there be truths in this area? If there have been any great and selfless benefactors in recent decades, you are undoubtedly one of them. You have helped many people and artists, and have taken up community causes that few have undertaken as individuals or businessmen: for decades you have financed the only Hungarian-language daily newspaper in South Partium and Banat, Nyugati Jelen, and you have also founded the journal Irodalmi Jelen, which has long since outgrown the borders of the region. In other words, you do not accumulate wealth for your own sake, but you feel a sense of community responsibility, and you devote a lot of money to these tasks. Why?

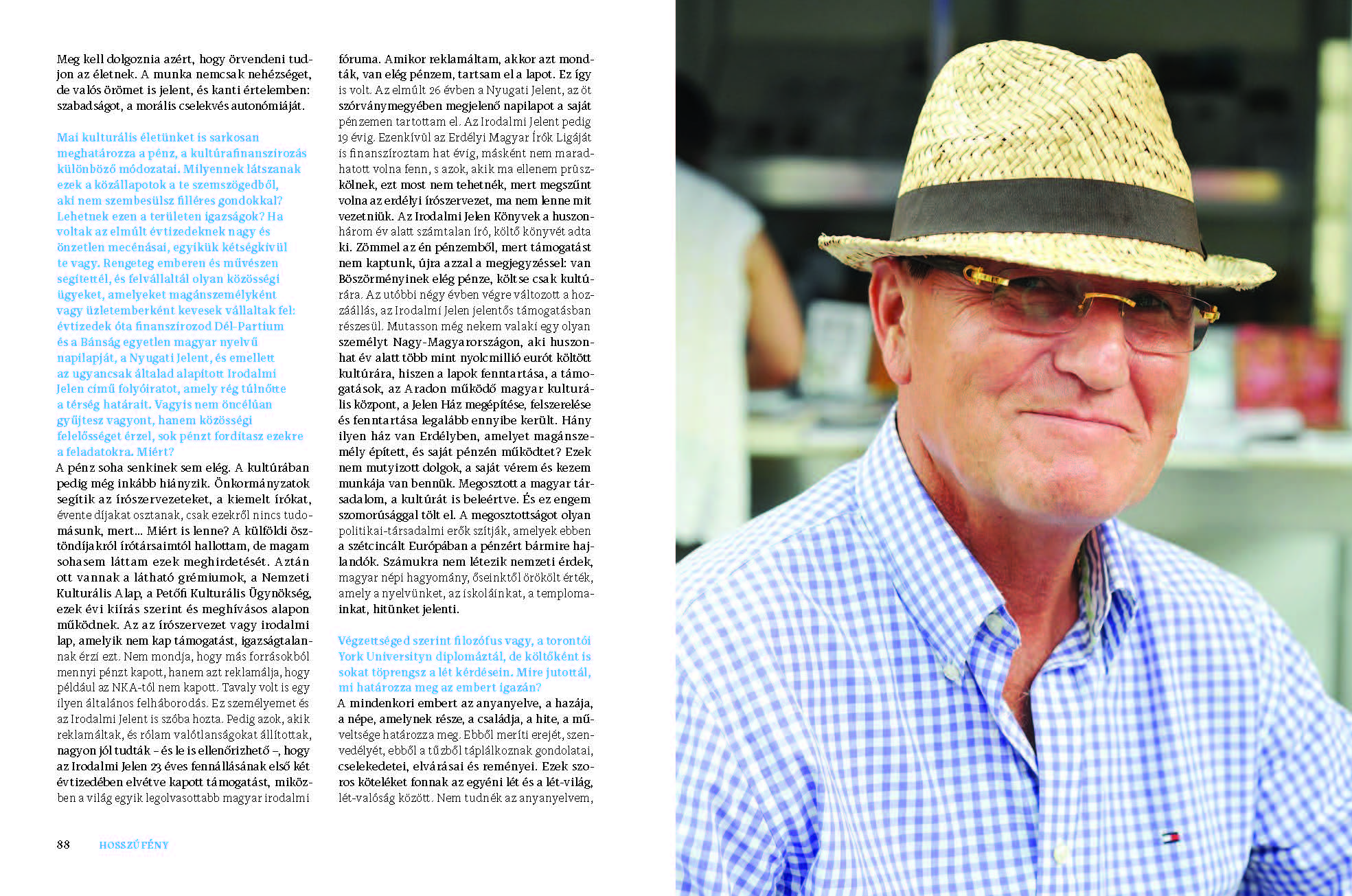

Money is never enough for anyone. And in culture, it is even more lacking. Municipalities support writers' organizations, outstanding writers, they give out annual awards, but we don't know about them because... Why should we? I've heard about scholarships abroad from fellow writers, but I've never seen them advertised myself. And then there are the visible bodies, the National Cultural Fund, the Petőfi Cultural Agency, which operate on an annual basis and on a call for applications. A writers' organisation or a literary magazine that does not receive funding feels that this is unfair. It does not say how much money it has received from other sources, but complains that it has not received from the NKA, for example. There was a general outcry last year. It was about me personally and about the Literary Report. Yet those who complained and made untrue allegations about me knew very well - and it can be verified - that Irodalmi Jelen has received very little funding in the first two decades of its 23-year existence, while it is one of the most widely read Hungarian literary forums in the world. When I complained, I was told that I had enough money to keep the paper going. And that was true. For the past 26 years I have been maintaining Nyugati Jelen, the daily newspaper published in five counties in the region, with my own money. And the Literary Journal for 19 years. I also financed the League of Transylvanian Hungarian Writers for six years, otherwise it could not have survived, and those who are now railing against me could not do so now, because the Transylvanian writers' organisation would have ceased to exist and they would have nothing to run today. In the twenty-three years of its existence, Literary Present Books has published countless books by writers and poets. Mostly with my money, because we received no subsidies, again with the comment: Böszörményi has enough money, let him spend it on culture. In the last four years, attitudes have finally changed, and Literary Journal has received substantial support. Someone else show me one person in Greater Hungary who has spent more than EUR 8 million on culture in twenty-six years, because the maintenance of the newspapers, the subsidies, the construction, equipment and upkeep of the Hungarian Cultural Centre in Arad, the Jelen House, cost at least that much. How many such houses in Transylvania were built by private individuals and run with their own money? These are not mutilated things, they are the work of my own blood and hands. Hungarian society is divided, including culture. And that fills me with sadness. This division is being fuelled by political and social forces that are prepared to do anything for money in this torn Europe. For them, there is no national interest, no Hungarian folk tradition, no value inherited from our ancestors, which is our language, our schools, our churches, our faith.

You are a philosopher by training, a graduate of York University in Toronto, but as a poet you also ponder a lot on the questions of existence. What do you think really defines a human being?

A person is defined by his mother tongue, his country, the people he is part of, his family, his beliefs, his education. It is from this that he draws his strength, his passion, his thoughts, his actions, his expectations and his hopes. They weave a close bond between individual existence and being-world, being-reality. I would not know my mother tongue,

"I believe that everything can be achieved with pathos, fire, passion, strong will, hard work and dedication. "

Living without my country. For me, home is what I can identify with every day, where my victories, my doubts, my actions, my thoughts are born. It is where I live all my joys, despairs, successes and crises. In ontology, only what we struggle for, create and pass on makes sense.

What do you see as the greatest challenges and tasks of contemporary art today? What should we be, or in what direction should culture be moving in order to be, say, a hundred years from now have a well-defined Europe?

I wonder what Kálmán Mikszáth, Géza Gárdonyi, Zsigmond Móricz, Áron Tamási, Dezső Kosztolányi, Albert Wass, Dezső Szabó, Mihály Babits, Lőrinc Szabó, Zoltán Zelk, Sándor Weöres, Sándor Csoóri would say to these two questions today... The arts are a reflection of the human, economic, social and political judgements, feelings and moods of the time. It is a priori and apodictic, i.e. irrefutable knowledge: for a nation to survive, it needs offspring, children. A nation, however large, that does not take care of this is doomed to die sooner or later. We must invest our strength, energy and money in our own children. It is absolutely insane that I, as a man of the 21st century, should have to deal with the aggressive will of an invading minority, to take it upon myself to raise it to the level of my social consciousness. What is happening in Europe today is simply unbelievable. Please read my novel "Regal" (Thousands of copies have been sold in German and English.) It will tell you how immigration to Australia, Canada and the United States took place in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. What criteria were used to allow Eastern Europeans to immigrate to these countries. If someone had tried to complain, speak out, shout, throw stones, attack police officers, they would have been deported back to where they came from, but only after they had served their prison sentence for those actions. Here and now chaos reigns. Thousands of years, centuries of social and human values are gone, and some hysterical, crazed, unnatural will is beating our heads against the ground if we do not agree with the aggressive, often anonymous immigrants and their supporters who want to bring Europe to the brink of total chaos. I do not know what lies ahead. We are not a nation with a large population, barely ten million at home in Hungary, and another five million or so scattered in the breakaway territories and the wider world. The only thing we can do is fight and hold on as long as we can. We have been a nation-building state for more than a thousand years. Let us remain one!

And where do you see Hungarian literature in the European definition?

I am not worried about Hungarian literature. We have countless contemporary writers and poets of outstanding achievement. I see no problem with the supply of new talent. We just don't have the soul-destroying, ideological divisions among us that sap our strength. Above all, democracy requires discipline. Many people forget that. And it requires a lot more, including a large dose of humility in the good sense. Let us listen to each other. Let's debate with real, demonstrable reason, not with obscenities. Let us not be driven by emotions, by artificially manufactured, false arguments, by insults, by making fun of the people of the countryside, who live here, not in another isolated country. Where does this superiority come from? Hungarian is an integral part of European literature. Despite its particularity, our literature has always been embedded in Europe. Therefore, I feel that we have a common destiny. What destiny exactly? I would not dare to predict.

What would you most like to leave behind after you?

With my writings being about life, I hope I have established a thing or two from which others can learn and learn from. What I regret is that I have spent so little of my time on literature. I could have written many things when I was young. But then I did not have that time. For decades I had to do other things to support my family and myself. For a decade I lived in Canada, in exile. My other great pain is that I have written very little about the Hungarian people, about Hungarian life, but wherever I have travelled and lived in the world, I have always seen countries through their eyes, and I have seen their fate in everything.

What was your childhood like?

I grew up in a poor family. My maternal grandmother used to bring home oil from the canteen in a decisive bottle. It was usually half full. From my time at the Cluj Ballet Institute from 1961 to 1968, all I remember is that I was always hungry. I didn't get any parcels from home like the others from their parents who were better off. The only food I got was what was given to me in the canteen of the institute. I ate a lot of brown bread and drank water. I know from experience what it means to be hungry. These memories cannot be forgotten. They live like a warning fire in my mind. Now that God has given me enough money to live on, I feel it is my duty to give back some of the money I have worked so hard for to the Hungarian community that I love with all my heart and of which I am a member. Giving is always a greater joy and satisfaction than receiving. I have helped countless people, writers and organisations over the decades. Even those who have turned against me or even refused me know this. It hurt at first, but now I am at peace with the idea. I have done nothing to be thanked. The bad is always remembered, the good is soon forgotten.

In terms of literature, what do you believe in? I suppose you have a poetic ars poetic, and you have a businessman's ars poetic as well...

I believe in doing everything with pathos, fire, passion, strong will, hard work,

with dedication. In the end, literature is a craft. The fact that not everyone is a huge success, not read, not rated, does not detract from the value of their literary work, if it is truly significant. One way or another, everyone gets there. And remember, there are flowers in spring and there are flowers in autumn. Literature is a very sensitive instrument. It balances on the border between reality and dream. As Sándor Márai would say, the characters in a novel look back at the one who brought them to life. The writer interacts in a strange way with those he has created, who suddenly say hello back to him, and he finds himself influenced by their existence as writers. I believe, along with Marais, and perhaps many other fellow writers, that literature is magic, magic.

How do you create? Can you spontaneously switch between the mindset of a creator and a businessman, or do you have to consciously set aside one or the other as the situation demands?

Any writer who has something to say for themselves creates because they have something new to say about something that has been written about countless times for millennia. This is what Aristotle writes about in his great essay, The Poetics. Social, political and economic changes always bring something new about the human drama, whose basic situations remain the same, only the circumstances are different. If God did not live in us, he would not say hello back to us. I am an extremely restless person. It affects my state of mind fatally. I say fatally, because so much of what I plan remains on my "workbench". Important things fall out of focus and I can only return to them by a miracle, if I return at all. But what is important is that I am not only living in this world, but I am building worlds myself. In my judgment, very meaningful and exciting worlds. I've had no brain for business for several decades. So I have nothing to put aside, I focus on one thing and that is literature.

Farkas Wellmann Endre