"LIKE IN LOVE, EVERYTHING IS OF THE MOMENT"

Behind the scenes - answering questions from Melinda Varga.

- You studied at a ballet school until you were sixteen. What does dance mean to you?

Dissolution in time. Spiritual refreshment. Freedom, floating. Imre Dombi, a teacher at the Cluj-Napoca Ballet Institute, described the steps of character dance and even folk dance. I was struck by the fact that there is not only a written copy of the word, but also of the movement, the step. I was a student at the ballet institute for seven years. I wanted to be a choreographer. At that time, my role model was Maurice Béjart.

- Later you wanted to be an actor. What motivated your decision?

I suspected a challenge in acting. Today I still like to recite. Did it come to nothing? It wasn't up to me. György Kovács, the great master of Transylvanian Hungarian acting, was the jury president the year I was admitted, and he took me through the exams. In the end, the rector of the Szentgyörgyi István Szentgyörgyi University of Dramatic Arts at the time downgraded my Hungarian literature paper so that someone else could get into the university instead of me. But the person he got in did not become an actor, but a director. He is also mediocre.

- Who is your favourite actor?

Éva Szörényi and Antal Páger... and Hilda Gobbi, Mari Törőcsik, Gyula Kabos, Manyi Kiss, Kálmán Latabár, Éva Rutkai, Zoltán Latinovits, Tamás Major, Iván Darvas, Imre Sinkovits, Péter Huszti... and I could go on and on. I am a great lover and admirer of Hungarian theatre.

- Which film was the film of the year for you?

Ildiko Enyedi's The Story of My Wife, based on the novel by Milán Füst.

- After two books of poetry you had to flee abroad to escape the retribution of nationalist communism. Was it a blessing or a curse in retrospect?

Both. Flight is fear, fear of the unknown, fear of the uncertain. It's an extremely desperate condition. In my novel, Regal, I wrote an episode of my story. It will be published again this year. It was a blessing, the new world, the taste and smell of freedom like nothing else.

- You have become one of the best known and most successful business owners in the country, after a lot of hard work and struggle, and before that you were in business in Canada. How did the writer and poet in you feel about that? Did he never protest?

My God, how far away from me is the battlefield of the business world! The constant worry, the body-soul consuming anxiety that we will build even this lamp, that meter, that we will even light up this market and the neighbouring one with our products, while we light up five other Romanian cities. But in all my successes, there was also a seed of failure. I hope that the Almighty will give me time to write about the vicissitudes of my life as a factory owner and businessman. As for the poetic protest, no, that never happened. By the end of the day I was so exhausted I had no thoughts left.

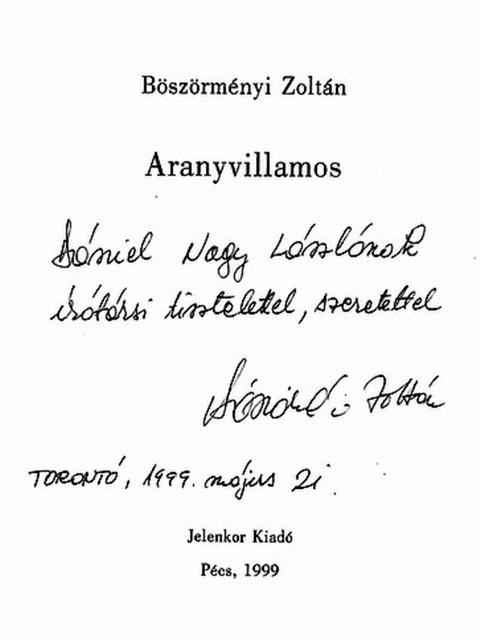

The Toronto radio site preserves this dedication from the 1999 edition of the Golden Fleece.

%20c%C3%ADm%C5%B1%20%20essz%C3%A9reg%C3%A9nnyel.jpg)

- Did you ever think of a poetic image in a business meeting?

Once, in Fortaleza (Brazil), where I was going to buy a factory, one of my negotiators, who found out that I was Hungarian, asked me about the polyhistor Sándor Lénárd. That was the only time anyone's name ever came up in connection with literature.

- You studied philosophy at York University in Toronto. Why were you interested in the philosophy faculty?

I chose philosophy because of the logic. And also - I was (one of) the managers of a car dealership in Toronto - because I could use what I learned at university in my workplace. I used the power of persuasion and argumentation as a working tool in sales. My short novel published this year, While I Think I Exist, is about this.

- You have two major novels, three short stories, two short story collections and countless poetry collections. Do you have a favourite?

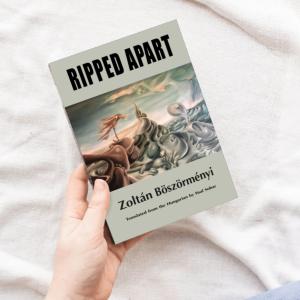

A parent loves all his children. And as it happens, the youngest, the last born, is always the dearest. This applies to my novel Torn to Pieces.

- Which of your books was the hardest to write?

I find it hard to write. It takes me an awful lot of time to get ready for a major piece of writing. I struggle a lot, I think, and every time I look at the white space of the screen, I am terrified. Perhaps I wrote my novels "Regal" and "Yearning" in the midst of the greatest emotional pain.

Readers waiting for a book signing at the Moscow book launch

- Which of your books translated into foreign languages do you like best?

I have great translators. Pál Sohár, who is also one of my best friends, has been translating almost everything I have written into English for almost twenty years. And so far everything he has translated has been published. Yuri Gusev has translated my writings into Russian. I value his friendship very highly. Raoul Weiss interpreted in French. My most recent book of poems was published by Sygne Publishing in Paris. Hans Henning Paetzke has not only been an excellent translator but also an excellent manager of my books in German. Immer wenn ich meine Augen schließe (Always when I close my eyes) was a success in Germany. I also have two excellent Romanian translators, Ildikó Gábos Foarță and András Dosa, the latter of whom translated my novel Torn to Pieces into Romanian. I also have Spanish, Swedish and Polish translators, but they have only worked with me on one book each.

With Hans-Henning Paetzke at the launch of Notlandung at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2019

- What decides whether an impulse or life event becomes a poem, a short prose or a novel?

As in love, everything is of the moment.

- You founded the Irodalmi Jelen in 2001. What motivated you to create the magazine?

After Zoltán Franyó's Genius and Új Genius in Arad after Trianon, and after the literary magazines Periscope, edited by György Szántó, between the two world wars, I wanted to create a publication that would last for decades. Another important goal of mine was to become a national (I mean historical Hungary) literary magazine.

With György Faludy in Arad in 2005.

- You knew György Faludy well, who was a regular contributor to the paper. How do you remember him?

We met as residents of Toronto. I did two interviews with him for the international broadcast of CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) radio - now no longer broadcast in Hungarian. He was a walking encyclopedia, talking passionately for hours about literature, politics, love. His friendship and love made me privileged. He volunteered to be the chief editor of Irodalmi Jelen. He was the first to send his manuscript to the editorial office every month. His humour and intellectual power dazzled me.

- Literary Review is now in its twentieth year. What would you highlight from these twenty years, what is the most significant for you?

The feverish devotion and passionate fervour of my colleagues. Without them, I would not have been able to achieve everything I set out to do. Over more than two decades, we have published the work of nearly three thousand authors. But, most importantly, we have (also) become a writing workshop for young people.

.jpg)

With Zoltán Bene, the magazine's prose editor, at the Literary Present awards ceremony in Arad in autumn 2021

- Why do young people also read contemporary literature?

First of all, because contemporary literature reflects the times we live in. Also because we have many exciting poets, prose and essay writers, and many talented young writers.

- Why do you love the sea?

I have yet to meet a person who doesn't love the sea. The sea is a symbol of freedom, of boundless hope, of longing

- What is the best word for the sea?

Ever-moving sailor. (Wordplay in Hungarian)

Fishing in Barbados

- Do you fish?

So far, every time I've been out in the Atlantic, I've caught fish. A lot!

- You play sport regularly. Does sport help with your writing?

It helps. Sport calms me down, it takes away the bad energy I've built up. A certain physical catharsis.

- You like tennis. You've practised the sport. Who is your favourite tennis player?

My Barbados tennis coach passed away from the shadows more than two years ago - at a very young age. I have not played since. My favourite tennis player: Novak Đoković.

- You like historical subjects. If you were a general, an emperor, a tsar, a king or a prime minister, whose skin would you most like to be in?

Nobody. I'm happy with my own skin.

.jpg)

The Barbados landscape, photo by Zoltán Böszörményi

- You know the female psyche well, and the female characters in your novel Torn to Pieces are authentic and compelling. And in your short novel, Longing, you take on the role of a little girl. What is the most difficult thing about voicing female characters?

My female characters are always me. So I never struggled with voicing them.

- How is a character born, how do you give her a name, for example?

They are given a name according to their mental and physical ability. And in The Waiting for Salt, the dying girl has no name. She just lies in her hospital bed and remembers.

- Is it easier to draw women or men?

Neither is difficult for me.

- Do you dream with your characters?

A lot. I wake up in the morning to find one or other of them arguing with me in my dream. I don't always remember clearly what they accused me of or what they wanted. It's a particularly strange situation. When I write, I try to recall their words, to describe their gestures.

- Have you ever dreamed of writing a poem or a short story, a novel idea?

- No. Never.

It's been published: Irodalmi Jelen, 2022. február 26.

Translated by Deepl.