Coming back Home to Literature

“It reads like a novel,” one could easily say about Zoltán Böszörményi’s life story. The author started out in Transylvania, went through the basement torture chambers of the feared Securitate (Romanian Secret Police), and then emigrated overseas. Returning to his native land much later he established a daily paper for the smaller Hungarian communities scattered over five counties of Romania (in an area that had lacked such service) in addition to a Hungarian literary journal with the largest circulation anywhere in the world.

Although you had published two volumes of poetry in your twenties before embarking on the successful career of a entrepreneur abroad and at home, what made you return to the written word?

My return was not the result of a hasty decision. This area here is dear to me, these trees, these fields are mine. And how could I forget that I was raised in literature and the love of the language by masters who have since become major figures in Hungarian literature, such as Sándor Kányádi and Aladár Lászlóffy, and I started out with such authors as Géza Szőcs, Zsófia Balla, and Attila Mozes, even though destiny had other paths for me. My second volume of poetry had something to do with that.

Why did “Title Suggestions”, your second volume of poetry, represent a threat to Socialist Romania?

The book had a few veiled references to nostalgia about historical Hungary and thus it was declared anti-Romanian and irredentist. The Securitate officers kept me in a dark basement room for eight hours and finally asked me if I’d ever seen a fatal traffic accident. Yes, I said rather petulantly, but then their next question was How would I like something like that to happen to me? They were seriously thinking about killing me, it was clear to me. In the final analysis, it was my “Title Suggestions” that prompted my emigration to Canada.

How did you go about trying to fit in there?

I got a lot of help from the community associated the Hungarian House of Toronto, headed by József Ormay and his wife from Transylvania. It was reassuring for me to see how they had dealt with the problems I was facing then. Soon I was doing the Hungarian-language radio show in Toronto, I graduated from college, and eventually I started my own business.

What business?

We produced brand names and company logos. In the first two weeks the business brought in a check for six thousand dollars. I photocopied and enlarged the check and had it framed, but I did not sit on my laurels, I had bigger ambitions. As it happened, the summer of 1991 was very hot in Toronto and the economy, too, was in the doldrums. I decided to go back home to Transylvania and visit my parents after eight years. Back home somehow I got the impression of walking on hundred-dollar bills on the sidewalk, and all I had to do was bend down and pick them up.

Let’s skip ten years and back to books…

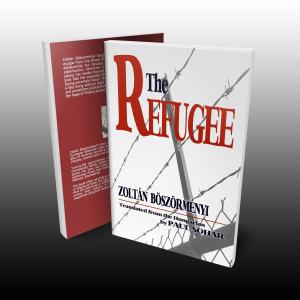

In the past two years I had plenty of time to write a brand new volume of poetry. I had to give up some of my business involvements suddenly. Where else can one find refuge under these conditions but in words? “The Golden Tram Part III” reflects some of these issues. Since then I have published yet another poetry book, “The Skin of Nothing”, and while in Barbados I finished “Far from Nothing”. It’s a parable of man’s eternal struggle, told in terms of a man trying to find his niche in the world in spite of all odds, as circumstances conspire against him.

Is the book about your own quest?

No, not really. There’s nothing autobiographical about it. The faintly flashed story takes place in an unnamed place. The idea was to emphasize the tragedy of modern man, how he would like to snuggle up to someone, to feel good about himself, to love someone, and yet, at any time he can find himself alone and despondent. He has to help himself first of all, to find the inner strength that will help him move on after he digs himself out of the everyday problems. The book is only 200 pages long (150 in ms). I feel today’s world requires short and action-packed books, so that they can be read in one sitting, and the reader can say afterwards that he or she got something out of it. The book has philosophy, ideas, action, and tragedy, and of course it does not lack that certain catharsis described by Aristotle in his Poetica. That’s how I see the twenty-first century novel.

by Norbert Haklik, Magyar Nemzet