Something Close Up

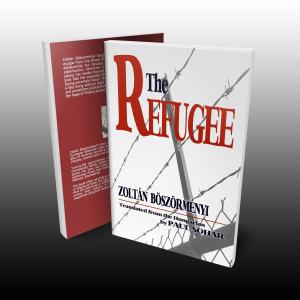

Comments on “Far From Nothing”, a novel by Zoltán Böszörményi, translated from the Hungarian by Paul Sohar, published by Exile Editions, Toronto, Canada

In its birthplace, Hungary, this book had an interesting sales curve. The initial rise soon gave way to a drop for a month or two before it took off again to reach bestseller status. Clearly, the best sales force, the word of mouth from the readers, was at work. In the meantime this first novel garnered some clever and controversial comments from a few erudite critics and yet, it seems to me, (a very thorough reader indeed, by definition, as the translator), one piece of its puzzle is still missing. What’s the puzzle? you may ask. Why, the puzzle of its eventual success, and I don’t just mean sales figures alone but the way a book by a newcomer on the literary scene was obviously able to stimulate its readers to debate the work, taking strong positions for it or against it. And the way many so-called literati still try to evade the whole issue.

They don’t know what to do with this book, it’s beyond their accustomed scope of expertise.

Don’t ask me to hold up the missing piece here like a smoking gun, only let me point out a few unusual features in this novel that I feel may point the way to the missing piece.

The most unusual feature I want to highlight first of all is a missing one; the people in this novel lack ethnicity, starting with the main character, Rudolph. He is a blank spot as far as the ethnic map of the world – his world – is concerned. And so are all the other principals. They are not identified by their background, nationality, race, color, religion, or any other group characteristics. They are all individuals, described by their personal habits and appearance only, and let loose in limbo. Yes, in limbo, because we are never told which part of the world we are in, what city, what country.

Should this obviously intentional omission be taken as statement about the global – or the increasingly globalized – world we live in now? Are we all generic, Brand X people, running around like ants? Is the global village an anthill? Or are we more like cockroaches?

That should put us on the right track. Cockroaches. Did Kafka’s Herr K have a religion or ethnic identity? Even the location of his travails remained unspecified. It didn’t even say if it was a kingdom or a parliamentary democracy or an outright dictatorship. The story would have fit in any of those systems of government. It never occurs to the reader now to question why Kafka didn’t add to the woes of Herr K that he was a Jew, like himself, and a German living in a Czech environment, like himself. It would not have helped Kafka as a writer to explain away the troubles of his (anti)hero. We like Herr K the way he is, unidentified, a man without roots, without direction. Herr K is the quintessential global man, the Brand X individual, stripped of any insignia of ethnicity or religion. Kafka was a visionary in the way he foresaw the trends of twentieth – and twenty-first – centuries. He could look well beyond the provincialism of his time and see the modern world in the making – or was it a world of all times? – and see man as an individual human being with his personal pains and cares and anxieties, and see him without the questionable(!) support of an ethnic group around him.

The genius of the Böszörményi book is to bring out all these points in high relief and without the escape hatch of a surrealist world. “Far from Nothing” gives a stark picture of man trying to make his way in this global world, without ideology, without ideals, without an identity, without a fate. Rudolph hasn’t a clue as to what weapons are marshaled against him and what dark forces he has to fight. He has plenty of business savvy and good understanding of human nature; shouldn’t that suffice to survive in the business world where he operates? Plus he’s a student of philosophy; isn’t he well prepared to meet the world head on?

Even though married, with one child, and with a business career well under control, Rudolph is all alone in the world and vulnerable, subject to panic attacks and bouts of claustrophobia and, worst of all, he’s unaware of the roots of these problems. Studying philosophy and logic, he digs deep into the thoughts of those before him, but he cannot realize that there is something basically wrong with the picture he has of the world.

He may be without a clue, but not without an unexpected resource. Wanda. Yes, in this rootless, dissociated, alienated society the only thing that can bring people together is sex. The shared experience of pleasure and temporary fulfillment. Living in a global anthill, stripped of our identity, our ethnicity, religion, family background, all we can rely on , the only way we can reach out to other lonely individuals is via sex. This primitive – no, more than primitive: primordial! – way of communion/communication, of coming together and feeling other people’s existence while reviving one’s own awareness of existence through the physical act; the shared excitement of the physiological response, reawakens the psychic sensation of a bond between two individuals and thereby reasserts the bond to all humanity, or at least the possibility of such a universal bond that we seem to have lost in the machine age. At the same time, in the sex partner, another person outside of oneself, one meets a representative of society at large, a live individual in this environment imbued with and built out of virtual reality, and through that person one regains a sense of reality of oneself and other people as well. There’s a feedback from the partner that is the essential element in the sex game, this ancient ritual we share not only with our ancestor but the whole living world, from monkeys down to the humblest creatures.

Böszörményi proposes this basic human function – not just a base instinct in his estimation and descriptions – as the only way for the solitary individual in this global anthill to come alive as a social animal, a member of society, a constituent part of humanity. Consequently, his book offers generous helpings of sex – but never crude pornography, never a four-letter word. It’s in the bedroom where he diverges from Kafka’s bleak world; Böszörményi’s Brand X hero, although just as alienated from the anthill and just as amnesiac about his background as Herr K, does not accept his lack of identity, and he is not as fatalistic as Kafka’s characters. He wants to reach out, and he does succeed in building a bridge between himself and the outside world, at least for a while and within the close confines of Wanda’s bed.

But Wanda, too, is a blank spot; except for her physicality, she’s as fateless and lacking in identity as Rudolph. They are two feral creatures that bump into each other in the jungle of contemporary urban life.

It is not only sex that Rudolph has at his disposal as a way of stepping outside of himself, of transcending his isolated, anonymous existence. He has philosophy; he has Descartes to guide him into the world of ideas, into the labyrinth of ratiocination; in a word, he’s fortified by the potent brew of reason. At first the intermittent gymnastics of the intellect seem abstract, sterile, and more like a puzzle, a diversion from more mundane concerns, but slowly the intellectual acrobatics become integrated with the storyline as events start to accelerate around Rudolph. And willy-nilly the reader too gets drawn into game, puzzled by what seems like an experimental device, a post-modernist conceit, these philosophical flights of thought inserted into the flow of the developing drama. Certainly, an unexpected departure from the usual, especially in the life of the anthill. Can philosophy provide the missing piece or, at the least, make up for the lack of individual definition? Or is abstraction introduced only to emphasize the isolation of the individual?

Kafka forces his hapless characters into a distorted use – or rather, abuse – of their intellect, into the obsessive effort of trying to solve impossible problems or problems others do not perceive as such, in an effective demonstration of the uselessness of the intellect; coping with the anthill requires the abortion of reason. And yet the result is guaranteed not to overcome isolation and alienation but to deepen it. The individual is at the mercy of unpredictable forces and the undecipherable rules of the anthill; in the end, even reason works against him. There’s no way out, life is a vicious circle, a devilish merry-go-around, it doesn’t matter where you get on or where you try to get off. Your efforts, whether mental, physical, or spiritual, are useless. As Rudolph’s story progresses, Kafka’s and Böszörményi’s paths converge. Philosophy offers no better understanding of this world than the pigeons in the park; all it can do is raise your level of consciousness and thus enable you to take a respite from the mindless task of building the anthill.

It would be interesting to speculate as to how it would have affected his writings if Kafka had discovered sex, and I mean a full-blown (no pun intended!) relationship like between Rudolph and Wanda. While in Kafka’s world sex remains a surrealist monster, it becomes the only reality in Böszörményi’s version of the modern vision. In fact, sex – or gender, in more politically correct terms – is the only identifying mark the people of this story bear, who otherwise appear as figures in a dream, with faces blurred, either veiled or turned away. This generic form of humans gives the novel an unreal feel, turning it into a parable , a tale with a hidden message. Sex is the only thing allowed to intrude into this twilight world of a modern metropolis and blow the mist away, pull the veil off the face of the hero and his mysterious Wanda – who is definitely a woman, but with such eagerness that it doesn’t let her be anything else. She is an iconic being, a foil to Rudolph’s manhood, the instrument that most emphatically defines Rudolph as a man. This definition though gives flesh and blood reality to the hero so that we care about him even as he flounders and at the end he almost automatically, like a well-programmed ant, starts the quest all over again. Will he succeed? Most likely not. The anthill, no matter how large and how global, has no exits, no way out.

This is a message that seems to hit home, and it must be the secret of the success of Zoltán Böszörményi’s first novel, “Far from Nothing”, among his fellow Hungarians. As now the book makes its debut in the English-speaking World, it deserves similar attention. The central theme of “Far from Nothing” has something to say that’s uncomfortably close to us, caught up as we are in the ever-accelerating life of the increasingly depersonalized global village.

Emile Fisher